The following is my most recent contest piece. The assigned genre was drama set in Paris and I had to include a mask. Although I didn’t place AGAIN, I received positive and helpful feedback. This piece was special for me and I hope you enjoy reading.

UNMASKED

I was part of the human snake, slithering through various roped pathways, preparing to declare or not declare certain possessions in the monstrous Charles de Gaulle Aéroport.

The simple accent mark in aéroport whisked me back to the image of her hair blowing across her face. I had brushed her auburn curls from her face and kissed her tenderly before tucking the locks behind her ears. We had then turned towards the camera and posed for a picture atop La Tour Eiffel. Our mission was to spend the summer imitating les tourists américains. We were sixteen.

The nudge from behind urged me to advance in line and replace my memories with the present. Although my feet shuffled forward, the rest of me remained in the Eiffel Tower listening to her light laughter once more as she leaned her head against my arm.

I stepped from the stale air in the aéroport into the city fumes to hail a taxi and wondered what awaited me in La Ville-Lumière. The City of Lights. Paris. Situated in the cab, I turned once more to gaze at another Charles de Gaulle Aéroport sign. There was a time in my life when every molecule of my hope was fixed on the namesake of this place.

**********

Weary from the journey and life, I dropped my bags just inside the furnished apartment, found a comfy recliner. This was my final sabbatical. I knew I would not return to the States at the end of the seven months’ leave; my chapter as pastor of Lakeview Church was over.

Paris heard my first cries and Paris would witness my final breaths.

The rain drops began trailing down the window beside my chair, hypnotizing me into a much-needed sleep. Soon, the sound of pounding rain manifested into blinding sheets of water slapping against my face as I hurried les petits enfants silently through the mud. The children were too scared to cry, but their small tense bodies radiated their terror.

They trusted me even though they didn’t know me. I trusted Brigadier General de Gaulle even though I didn’t know him. It seemed everyone’s hope rested in someone else these days.

After a few hours of trudging in the greedy sludge, we finally reached les grottes where Jules would soon meet us with supplies and then escort the children to safety in Switzerland. As we settled into the cave, I made my way around, hugging each shivering small body and whispering my standard consolation, “Tout est bien. M. de Gaulle et son armée, ils se battent pour nous,” while my heart pled with God to let it be true. Our only hope was that General de Gaulle was winning the battle for our freedom.

We huddled together the night long, patiently waiting for Jules. Just before dawn, I awoke with Jules’ face next to mine and his hand over my mouth.

“Les Allemandes sont ici,” he whispered. “Tu dois aller avec les enfants. Je ne peux pas aller.”

Although my fear mandated a negative response, I simply nodded affirmatively. I had only finished the journey once and that had been with Jules. I couldn’t go on without him, especially with the Germans nearby.

I glanced over at the little sleeping faces, each one adding a weight to my already heavy heart. Would I be able to deliver them safely to welcoming homes in Switzerland, unreachable by the mustached monster?

Over the past few months, Jules and I had survived being jammed together beneath floors, in attics, in caves, even under piles of cow manure, praying the Germans would not discover us and our clusters of small children. My whole life had consisted of following in my brother’s footsteps; these secret missions were no different.

Now, Jules’ footsteps would not be tangible; I would have to rely on my memory and my own ingenuity. Doubts ignited my fear. I needed more details from Jules. I turned to ask my brother the onslaught of questions I had about the stations between les grottes and the Swiss border, but he had vanished.

I began quietly waking the children, making sure they saw my index finger pressed against my lips. They may not have understood the world’s events, but they understood that their lives depended on placing obedience above fear. I shared what remained of a baguette with their hungry bellies before exiting the cave.

Moments later, a battery of shots pierced the air followed by German voices fraught with anger, or was it fear? No matter which. They deserved to feel both.

After all was silent, I envisioned my brother crumpled on the ground, blood mixing into the mire. I quickly erased the image and shifted my focus on recalling the treacherous track to safety.

A clap of thunder brought me to my senses, and I awoke. I sat for a while, my eyes adjusting to the dusky light. Taking deep breaths, my shaking diminished. This recurring nightmare never lost its impact, no matter how often it came to me. Looking around the living room, my familiar loneliness loomed before me.

I was in the City of Lights, but I was more familiar with darkness. On this day, I decided not to shake off the nightmare, but to examine it. Maybe I would be able to find and destroy the terror it cradled.

The first of many journeys without Jules was the substance of that particular nightmare. Not knowing if he was dead or alive, rotting in a makeshift grave or suffering unimaginable torture in a prisoner of war camp. Maybe if I created a happy ending where my brother surprisingly returned to me unharmed, I could stop reliving that day. As a realist, I could not even begin to believe this as a possible ending.

Each of our journeys had originated in the Vivarais-Lignon region, an area offering temporary refuge for war refugees, mainly Jewish children. Situated along the Lignon River in southern France, the name “Vivarais” (would live) emanated hope.

At first, Jules and I escorted those in danger from Paris to the Vivarais-Lignon region, a plateau situated along the Lignon River in southern France. The small towns and scattered farms offered temporary safe havens for those destined for extermination camps, mostly Jewish children. As the war progressed, we began taking the innocent Nazi targets, from Chambon-sur-Ligne to the Swiss border. I never understood what threat children were to Adolf Hitler and his regime, but the fact remained that he was set on killing them and the Gaudin brothers, Jules and me, were set on saving them.

My thoughts were interrupted by my growling stomach, so I left my thoughts and combed my hair before walking down a typical picturesque Parisian street. A few moments later I was relishing in a genuine cup of café au lait and an honest-to-goodness croissant. How had I survived all those years on Starbuck’s faux coffee and grocery story croissants that were more reminiscent of a biscuit than a buttery, flaky, authentic French pastry?

Feeling refreshed, I made my way back to my new home to begin unpacking. But first, I decided to take a tour of each furnished room as if I were invading someone else’s private space. The tasteful artwork replicas reflected my favorite memories of life before Hitler: Monet, Renoir, Degas, and Matisse.

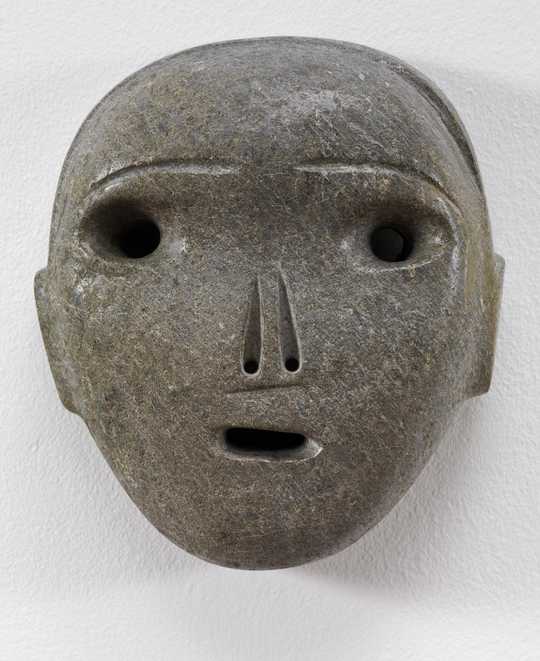

The small library housed several contemporary and many classic French authors. I ran my finger across the titles and then stopped at Dumas’ five-book series. Pulling the second book of the series from the shelf, I traced the gold-embossed title: Man in the Iron Mask. Masks are often used to cover something hideous, but in this story, the mask concealed goodness.

On the wall beside the books was a wooden mask fashioned similarly to the iron mask in the novel. Removing the mask from the wall, I felt a camaraderie, except my mask hid my shame.

All those years of living in the States married to Diane yet longing for Colette, portraying a loving husband felt wrong. I tried to be a good, protective father, hoping to make up for all those fathers who died in Auschwitz and other camps. I even did my best to shepherd a flock of parishioners to please God and somehow compensate for my pitiful life.

Behind each role, I was a broken man. A coward. A nobody. I had thought that serving God would redeem me from my cowardice during the war, but I never felt any redemption.

Replacing the mask on its wall hook and returning the book to its niche, I left the library and began unpacking. I knew where I would go first thing tomorrow.

**********

Watching Paris grow smaller in the rearview mirror, my heart pounded and begged me to turn back. However, after choosing the easy way for so long, I was determined to do two things before I left this earth. Ahead, was task number 1.

Arriving at my destination, I stood and soaked in the sign flapping in the wind: Welcome American Liberators! Men not born on this soil had come to our rescue when I was nowhere to be found. I should have been here with a gun in my hand and a helmet on my head. I then walked to the beach, sat down, and closed my eyes trying to let my guilt and shame blow away with the breeze.

Nothing happened, so I opened my eyes and drank in the beach. Anger rose from deep within as I thought about that day when the Germans were defeated. It wasn’t Eisenhower, Churchill, or my beloved de Gaulle who was responsible for the victory. It was those young men who first emerged from the ships to face a barrage of gunfire and explosives.

I should have been one of those men bursting from the belly of a battleship, not hiding under the floorboards of a farmer’s house with children.

There. I said it. I had silently lived with it for 50 years. Everyone had assumed I didn’t talk about the war because of the horrors I had witnessed. Nope. That wasn’t it at all. I had waited out the war with children in hiding places. Hiding places.

Sitting on the beach I wept for those who sacrificed their lives to set France free. I wept for my life I had wasted in hiding. I wept for Colette who remained only in a faded photograph I carried in my wallet.

My intentions had been to leave my burden of guilt and shame at the beach so my last days on earth would be peaceful. Instead, I felt as if I had taken on another greater burden of shame. Simply stating the truth had relieved me of nothing; it only invited more weight to hang around my heart.

After a long drive back to Paris, I wearily walked into my apartment. Turning to flip the deadbolt, I caught a glimpse of a letter that had been slid under the door. I carried the letter to my chair and turned on the lamp, then opened the handwritten note.

**********

My mind had been darting off in a million different directions since I first read the letter. The writer knew Jules. Did that mean my brother was alive? No. I could not let my heart believe that. Questions and suppositions badgered my mind.

I decided to skip le métro and instead walked to the Frame Brasserie. I was too nervous to drive. My reasoning was that the exercise would wear down the jitters, but the opposite occurred. By the time I reached the café, my voice ululated uncontrollably.

Seated at a quaint table near the sidewalk, I sat with my back to the Eiffel Tower. I couldn’t handle mixing thoughts of Colette in with everything else that might happen.

“Monsieur Gaudin?”

I turned to see a familiar face, yet I had never met this man before in my life. I rose and extended my hand all the same. The visitor pulled out the chair opposite me and sat down.

“You look familiar. Have we met?”

“Not exactly, but I know all about you, Oncle Gérard.”

“Oncle?” My heart jumped into my throat, and I was unable to utter anything more intelligent.

“I know this is a shock, but my father was Jules Gaudin. My name is Marc. I was three when the Nazis gunned down my father.”

“Somehow, I had always hoped that was just a bad dream.”

“I understand. He died somewhere between Chambord-sur-Vivarais and the Swiss border. My mother and I continued to pray for you after we learned of his death. Maman and I felt like we knew you even though we had never met you. Papa talked of you so much.”

“I didn’t know Jules ever married.”

“Oh, he didn’t. He and Maman were planning to . . . but then the war . . . you know.”

“I’m sorry about your father. He was . . .” The rest of my words were swallowed in sobs. These were the first tears that had fallen for my brother. I should have been embarrassed crying in a public place, but I wasn’t. Marc sat in reverent silence until I composed myself.

“How did you know I was back in Paris?” I asked as I tucked my handkerchief into my back pocket.

“I was finally able to track you through the network record keeper. I called your home two days ago and your son answered. He told me where you were. You really should call him. He’s very worried about you.”

“The network?”

“Yes. You know. The underground network that moved thousands of Jews and refugees of war. Did you know that my father was responsible for getting 898 children to safety?”

“898? Unbelievable! I never realized there was a network. I just followed Jules and then after he . . . after he was gone, Benoît always had a group ready to go when I returned to Chambord.”

“Well, you, mon cher oncle, you are credited with saving 1,015 lives!”

“What? Are you sure?” I thought back to those days and realized that after Jules disappeared, I had worked twice as hard to get children and adults to safety. Staying busy allowed no time for grieving.

“Saturday night, come to Le Grand Quartier at 7:00, Oncle Gérard. You can’t miss this.”

Before I could protest, Marc stood, shook my hand, and left me alone with my coffee and pastry.

**********

Exactly at 7:00, I crossed the threshold of Le Grand Quartier hotel and was ushered into the grand ballroom where Marc was eagerly waiting for me.

“I was beginning to wonder if you were coming. Here, follow me.”

The room was filled with people of all ages who halted their conversation and stared at us. Marc led me to the long table situated on the platform where I sat down and watched while Marc went to the podium and begin speaking.

“Ladies and gentlemen. This night has been a long time coming. Personally, I was beginning to wonder if it would happen at all. But thanks to the diligent work of Charlotte and Geneviève, we were able to locate most of the people on the list, and most importantly, mon Oncle Gérard.”

Incredulously, I listened to the words, but could not comprehend their meaning. The audience rose to their feet, clapping and wiping tears from their eyes. Stupidly, I sat gaping at them. My mouth hanging open.

Marc came to me and guided me to the podium as the applause began fading.

“I am proud to introduce mon Oncle Gérard Gaudin. Oncle Gérard, everyone in this room is here because of your bravery, your love, and your commitment to rob Hitler of his plan to destroy us. We would like to present you with this plaque in honor of your work of love. It seems so trivial considering the way you risked your life to save ours, but at least you can hang it on your wall and be reminded of your life’s most important work.

Applause erupted again. I hung my head and allowed the tears to flow freely.

Marc motioned for silence once again and continued.

“Inside this cherrywood box are letters from a large number of those who traveled with you, who huddled in caves, who were cradled in your arms as German soldiers marched across the bridge above you, who obeyed your every command because they knew their lives depended on doing as you said. We hope you find great reward in these messages of gratitude. We know of no man more courageous than you, Gérard Gaudin.”

For three hours, I heard their stories.

“I remember your stroking my hair when I cried for my mama.”

“Thank you for giving me the last apple. You must have been starving.”

“I often think about how safe I felt when you carried me across the creek.”

“I married and had four children. One is a doctor, another a nurse, my youngest son is an engineer, and my oldest is a police officer.”

“I still remember the feel of your thumb brushing away my tears and kissing my forehead.”

“Do you remember the funny story about the frog with three legs? You always told that story when we were so very tired of walking.”

**********

When I returned to my apartment, I fell to my knees in front of my chair and released my shame and soaked in mercy, gratitude, and a fresh dose of hope – not in another human, but in my Creator. I had found my redemption. I was a Gaudin, a son of God.

Before opening the cherrywood box, I went to the library where I removed the wooden mask from the wall and put it in a drawer. In its place, I hung my bronze plaque.

It took me three years and numerous handkerchiefs to read each letter from those who had traveled with me. I no longer felt shame that I wasn’t on Normandy Beach with guns, guts, and grenades. I had done my part in thwarting the evil plans of a tyrant by huddling beneath floors, in caves, and yes, even under piles of cow manure.